Italian lawyers denounce the repressive situation regarding the anarchist movement.

On 6th July, the Italian Supreme Court ruled to requalifythe double attack against the Carabinieri cadet School of Fossano that took place in June 2006 (two nighttime explosions that caused no injuries), from slaughter against public safety (Article 422 of the Italian code), to slaughter against the security of the State (Article 285 of the code).

The original offence, qualified as slaughter, carries a penalty of no less than 15 years’ imprisonment, whereas the punishment for the new offence is life imprisonment. It seems paradoxical that the most serious offence envisaged by our legal system was deemed to exist in this case, and not in the many very serious events that have occurred in Italy in recent decades, from the massacres of Piazza Fontana in Milan and Bologna train station and the Capaci bombing, to the via D'Amelio and via dei Georgofili bombings etc.

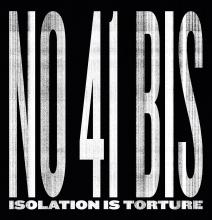

In April 2022, one of the two defendants was also subject to a decree for so-called hard prison, pursuant to Article 41 bis, paragraph 2, of the Italian Prison Administration Act (introduced in Italy’s penitentiary system to combat mafia associations, and aimed at preventing communication between the prisoner and their criminal association on the outside for criminal purposes). This is a noteworthy event as it is well-known that the anarchist movement inherently shuns any hierarchical structure and/or form of organisation. It raises the serious suspicion that the ministerial decree in question is intended to hinder political dialogue between a political militant and their milieu, rather than to prevent communication between a member of a criminal association with their accomplices on the outside.

In July, another harsh first-degree sentence was pronounced, when an anarchist militant was sentenced to 28 years in prison for an attack on K3, the headquarters of the Italian Northern League. Once again, there were no reports of harmful consequences of the incident.

In addition, in the summer of 2020, five anarchist militants were given a pre-trial custody order for terrorist offenses and spent around one year in in AS2 (High Surveillance, another "hard" prison regime), despite the very minor concrete actions they were charged with, such as unauthorised protests, defacement etc.

Other trials against anarchist activists are brought for crimes of opinion, for example, in two instances involving the Court of Perugia, where offences were qualified as incitement to crime aggravated by terrorism, as the defendants were said to have spread violent anarchist slogans; the same slogans and ideas that only a few years ago would have been traced back to the type of offence referred to in article 272 of the penal code, subversive propaganda. This article was repealed in 2006 on the basis that propaganda, including ideologies of violent subversion, must be tolerated by a state that calls itself democratic, lest it deny its very foundation.

Other judicial initiatives for associative crimes were brought against anarchist militants in Trento, again in Turin, in Bologna and in Florence, accompanied by a both widespread and incomprehensible application of precautionary measures in prison. The media narrative of the last two years, built on the basis of qualified statements given by the National Anti-Mafia and Anti-Terrorism Prosecutor, also depicts anarchists as instigators and responsible for the riots in prison in March 2020. This was recently denied by the ad hoc commission set up to establish the causes of the uprising. More generally, the recent half-yearly report produced by the Italian secret services, view anarchists – in a generic sense - as a significant social threat.

It is legitimate to ask what is happening in this country. Are anarchists actually posing a threat to public safety that must be met with force and sometimes an unscrupulous approach; or, as seen in past events, are they simply the new test case for an authoritarian restructuring of Italy’s political and democratic spaces.

The authors of this appeal are lawyers and directly involved in the defense of numerous anarchists in many trials. They are witnessing the increasingly widespread and casual removal of procedural guarantees from the above defendants. Specifically, in terms of the evaluation of evidence in regard to the subjective traceability of disputed facts; but also, in the abandonment of the criminal law of facts, in favour of a criminal law focused on the offender, which exalts the dangers of the ideology they subscribe to.

We are well aware that the birth of what may be considered a criminal law of the enemy is rooted in Italy’s recent history and lies in the legal actions directed at armed struggle organisations during the trials of the 1970s / 1980s. The approach was later extended to other categories of defendant (including migrants), following numerous emergencies that characterised subsequent years. The very same approach is being proposed today for anarchists who are guilty, above all, of manifesting their unwavering opposition to the established order.

As lawyers we are witnessing a “justicialist” trend that reserves one model of criminal legality for its citizens - with the accompanying guarantees and rights typical of democratic states - and another for subjects deemed dangerous - with strict provisions and measures, as well as differentiated prison regimes.

We find this all very worrying because it involves the penal system’s progressive departure from the principles of legal guarantees, from legality (where punishment is reserved for what one has done and not for who one is) and offensiveness, and marks a dangerous turn towards more preventative and neutralising functions, as the above examples demonstrate.

- So far, this document has been signed by more than 110 lawyers throughout Italy. -

Creative Commons by-sa: Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen

Creative Commons by-sa: Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen